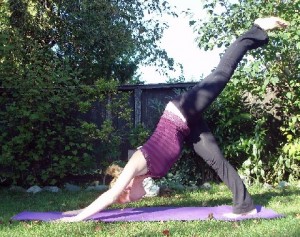

To add a challenge to your vinyasa, you can try this single leg variation. Feel free to switch to a two-legged vinyasa at any point during this sequence–some of the transitions are harder to do one-legged than others. Begin in a plank with one leg lifted. If you’re incorporating this into a larger flow, one-legged plank can follow naturally from downward facing dog with one leg lifted or from side plank with the top leg lifted.

Keeping the leg lifted, as you exhale lower slowly to chuttarunga. Keep the abdominals contracted, elbows close to the body, and shoulder blades sliding down toward the hips. In chuttarunga, the torso should not sink below the level of the upper arms as this can put the shoulders into a bad position.

Contract the abdominals to protect the low back, and as you inhale pull forward into upward facing dog. If you can, keep the leg lifted. Notice that you have to roll over the toe so that the top of the foot is on the floor. In upward facing dog the quads (muscle in the front of the thigh) are contracted so that the hips are lifted. Squeeze the shoulder blades back and together, and slide them down the spine.

This next part is the hardest. Rolling back over your toe requires you to use your tibialis anterior muscle in the front of your lower leg, and this muscle is often quite weak. You can lower the lifted leg here if you need to. Here we go: contract the abdominals (you’ll need them!) and as you exhale press back to a downward facing dog with the leg lifted.

From here you can go all sorts of places: pigeon? High lunge? A warrior? Handstand? That’s up to you!